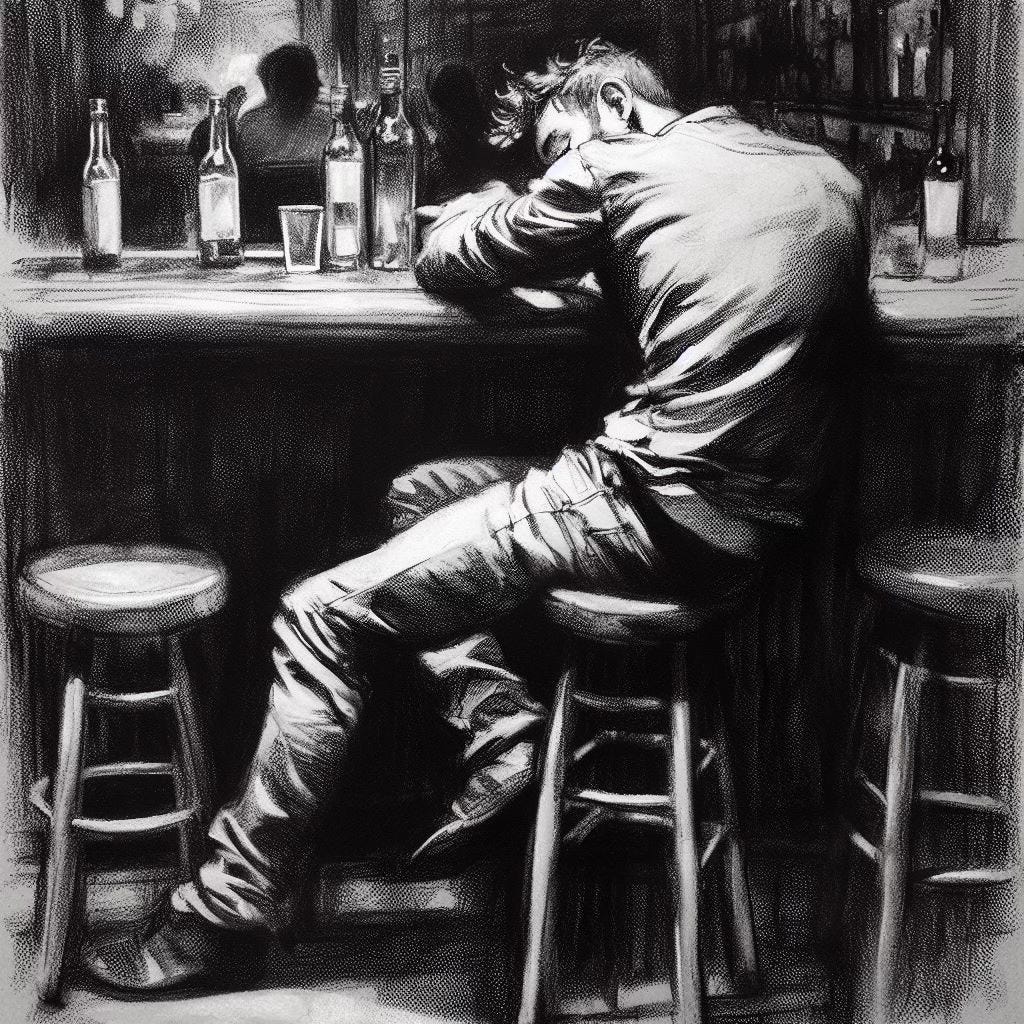

Morrison was always a good enough child when he was young, as good as kids could be, anyway. He never broke rules, at least rules that didn't deserve to be broken, and he always listened to Mum and Dad. When the sacred texts came out, he followed those rules, which had led to a good enough life. Yet, here he sat at the bar he frequented often, Satchet and Katt's, dejectedly playing with his glass filled to the rim with bourbon. A man was talking to him, but Morrison was only half-listening. The speaker was called Riddles; he never spoke in riddles, though, so nobody really knew why he was called that. Nobody believed that this was his real name, either. An important note is that Satchet and Katt's was not the kind of bar that got visitors. It was the sort of place that nobody knew when it was established, and no one recalled their first time there. It simply was and would continue to be; there would be no new clientele, nor would it lose clientele. So it is that many people believed, or at least whispered about, the fact that Riddles might be nothing more than the spirit of the bar because not a soul had seen him outside of the bar. Yet, everyone knew that this was, of course, silly, for nobody believed that spirits were real anymore. The Ancient texts had, of course, proven this.

So, we return to Morrison, only half-listening to a story that Riddles had told a hundred times, morosely toying with his drink. "So anyways, I says, I says, 'well Bonnie, if you'd wanted me to do that, you really should have told me first…' eh, eh?" he waited for his compatriot to laugh at the punch line. He grew a slightly worried look as he beheld Morrison. "Say Morrie... you feeling alright?"

"Huh? Oh, oh yeah, I'm just fine." Silence lapsed for a few moments, but then Morrison commented, "Say Riddles, do you ever just wonder what it is we're doing here?"

"What do you mean?"

"I mean... well, I'm not entirely sure what I mean," he thought for a second. "Why are we sitting here, at this bar, drinking, night after night, day after day? Going to jobs day after day, week after week. What's it all for? Don't you ever just want to watch the whole thing burn to the ground?"

"Burn what down!?"

"Everything! All of it, this society that we live in, the rules we follow, most of all that damned book!"

"Wow now, careful," Riddles hissed. "You don't know what you are saying."

"I am quite positive of my speech, and I mean it."

"Well then, you know that you're speaking blasphemy."

Flashes of emotion fluttered across Morrison's face—anger, sadness, anxiety, frustration, fear—which resolved into rebellion. "I don't give a damn who hears, I'm done with it, just plain done, I'm fed up!" He stood up from his bar seat, which led to his glass spilling, but he didn't care, his mind had taken to racing, and his body complied. "It's just a book!" he was now speaking not just to Riddles but to everyone. "It is just a book, and you have all been deceived! We can't even read it! They won't let us! Listen to your hearts, you fools." Everyone was quite taken aback by this sudden outburst from Morrison. "We can't be deceived forever; listen to your hearts, I say!" he cried one last time, then rushed out the door, into a bitter Perry Falls winter. The diner was quite for a few moments following the outburst, but as quickly as the gently talking was disturbed, it relapsed, and no one gave it a second thought.

Morrison stormed through the icy streets; his coat turned up towards the chill winds that blew through the town. His breath puffed into steam so that those who watched him walk by thought of a locomotive. His body remained conforming to the speed of his mind, driving as a locomotive through thought after thought. What do I do? Everyone is deceived, they do not know the truth! How can I show them that this thing is no more than a wicked fabrication? Is it even possible to do this thing? Will they listen to me? Yet, he realized deep down that its power over the human was too strong; after all, had it not ensnared him once? No, he needed to prove that this book was not infallible, that it was nothing more than a generation of human hands. This book was not inspired by the gracious hand of a god. It was not a gift to man but a curse to man gifted by Mephistopheles. How could such a thing? So he divined to steal it, to steal this sacred book, and thereby show the world it could be touched by mortal hands. He would show the world that man created it, and so man could destroy it. Then he hoped that his actions would speak louder than words, louder than the words of that book. They must! They would, they had to because he needed them to!

His head ached with the pressure of his ideas, the stress, the anxiety he was experiencing, so immediately his thoughts went to the book. He recalled the third principium, pain (in any form) is unnatural. The human body had evolved with perfection in mind, therefore uncomfortably was the indication that something was not at peace, thereby necessitating a remedy. The best remedy was FRX 120, a psychotropic drug. Morrison reached for the bottle, uncorking it as he had so many thousands of times. Then he paused, pills halfway to his mouth. Why are you taking this? He thought to himself. He had never questioned the process before, but this time, something in his spirit (though he did not know that) rebelled at this notion. So he dropped the pills back into the bottle and set the bottle down.

Samuel stood in the midst of the assembly, a small gathering of the rarest people on the continent. Those who believed that spirits could exist, those who believed in life after death in the area around Perry Falls were now 12. These 12 congregated in the house of Samuel, and as he stood before them, his breast boiled over with excitement. He looked around, fidgeting just a little bit, before grabbing a book out of his safe. The book was clearly old, battered horribly, with golden inlays. His palms sweated now, with nerves as he got ready for the reading.

He cleared his throat and began to read, "Ephesians 4 says this: 'I, therefore, the prisoner of the Lord, beseech you that ye walk worthy of the vocation wherewith ye are called, with all lowliness and meekness, with longsuffering, forbearing one another in love; Endeavoring to keep the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace. There is one body, and one Spirit, even as ye are called in one hope of your calling: One Lord, one faith, one baptism. One God and Father of all, who is above all, and through

all, and in you all… I'm going to skip a bit. A few verses later St. Paul says that we should henceforth be no more children, tossed to and fro, and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the sleight of men, and cunning craftiness, whereby they lie in wait to deceive; But speaking the truth in love, may grow up into him in all things, which is the head, even Christ; From whom the whole body fitly joined together and compacted by that which every joint supplieth, according to the effectual working in the measure of every part, maketh increase of the body unto the edifying of itself in love.'"

"Ephesians chapter 4 is one of my favorite passages in the bible. And it seems to me that many of us are tending to forget this passage of scripture; indeed we have entirely forgotten it. It's true that we are called to love the unsaved, but not at the bereavement of our fellow Christians. This Chapter here is not about loving the unsaved, but it's about the church ensuring that we remain strong within, that way we can love without!"

"That's true, Oliver, very true, good stuff."

"Thanks, Dan," he smiled at his friend. "It is no longer easy to remain a Christian; that much is certain. We are persecuted, and we are shunned, but the epistle of James tells us that we must rejoice in various trials. St. Peter exhorts us to do the same in many passages; after all, we shouldn't be surprised that we are persecuted. But the question is, what shall we do about it, how are we to behave?" He waited a moment for any responses, but the 12 around him sat waiting for the response eagerly. "Well, St. Paul actually gives us the answer. He says that when we come as a body to the unity of faith and knowledge in Christ, then we will not be tossed around and remain steadfast, and not be tricked and sleighed by man. But then we will be able to speak truth in love and we will grow up to and into Christ."

After he finished his little sermon, they played a few hymns from an old vinyl record player, they broke bread together, and began to talk more casually. Herbert spoke up, asking the group, "Has everyone seen that there is supposed to be a new edition of the DSM? The 8th iteration."

"Ha, ha! Of course, we have, and as always, no mention of the changes or expansions."

"Never! Only that it will be even better and even more thorough than ever before," rejoined Max, another member of the group.

Oliver, though, did not fully engage in this banter; he would add some quips every once in a while. Yet he tended to shy away from these conversations; it was a constant battle for him. He was passionate to help the fallen world of man yet did not want to be captured by it. Often though, when he removed himself or his opinion from such conversations, he was thought of as "snobbish." Simply put, he was not concerned much about it, nor was he unaware of it. He would listen to his friends discuss this unofficial state religion, but he lacked full interest in it. He hoped that he had struck the right balance of caring to not caring; in his estimation, it was a system in flux.

Dan continued, "I'm sure once the scientists have finished up the book, they will be more than happy to tell exactly what's different and exactly how to live life even better! Even more 'satisfyingly,' that is just what they always do."

"Yep," chimed in Frank, "I'm sure that we all are not having enough promiscuous sex or doing strong enough drugs; we are all in far too good shape. Eating too much meat and vegetables. All sorts of stuff, I am sure that we are doing wrong." He laughed.

For some reason, the conversation transported him back, some fifteen years ago, to the end of his college days. He was standing in a library, a life of carousing and revelry left behind him. More than that, a life of depression, sadness, a life one could call Nihilism, dead and gone. The BA in Philosophy had been sure to give a macro-dose of the famous German philosopher Nietzsche. So, Oliver found himself in a library, a book that he’d never really heard about before in his hand. A weird paperback copy of “The Books of Poetry,” a special edition printed version of Job, Proverbs, Psalms, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Songs. He had, of course, never picked it up if he’d known these were from the biblical canon. Yet, he was enthralled throughout the entirety of the first book, Ecclesiastes. Only halfway through did he realize that this must be from the bible, but he couldn’t stop reading. Here he’d been a philosophy major, and this great work of philosophy had never been offered to him. He felt cheated, but he also felt embarrassed for reading something mentioning “the sky’s spaghetti man.”

In the year 2080, there was no law against religion, other than the immense social pressures against it. One who believed in God would be mercilessly ridiculed, not jailed, but effectively shunned from society. Science had proven that God did not exist, and all that was left was the godhood of man. The prevalence of happiness as the land's highest virtue and suffering as the greatest sin.

Having believed that and taught the theories proving that, he now found himself reading these stories of great suffering. He felt… good, somehow better for having read them, in a different way, an inexplicable way. One that only later was he able to articulate, for so long had he fought and strove for his right to be happy, all the time. Now he decided, or rather learned, that he shouldn’t neglect his right to be unhappy. As the teacher says, “it is better to be in the house of mourning than in the house of mirth.”

He continued to reflect, remembering again when he first read those words, “vanities of vanities, all is vanity,” how that reverberated through his head, through his mind, his heart. His first thought was, ah, a forgotten writing of Nietzsche; however, he was terribly wrong!

“OLIVER!” his thoughts were interrupted.

“Yes… yes sorry, what?”

Dan pointed to the television set placed in the corner of the room; he also noticed that his phone was buzzing. A message displayed, “urgent announcement to be made by the secretary of public information.”

A pleasant-looking lady was speaking on the TV; she had a large new book in front of her, on the side emblazoned in white, read DSM-8. “Folks,” she said, smiling with fake enthusiasm but also concern, “Today we bring some terrible and incredibly worrisome news. The new manuscript of the DSM-8 has been stolen! How this was done is, as of yet, unknown, but it was scheduled to be released in just two months’ time. Now, why is this a problem? Don’t we have more copies of it? Well, yes, quite frankly, we do, but the concern here is, of course, the breach of government locations. Moreover, it is problematic and a worrisome anti-science sentiment. The DSM has worked wonders on the United States of America. It has drastically improved the quality of life, longevity of life, and overall satisfaction. So, the fact that somebody would question that or call that into threat is extremely worrisome. Fortunately, there are backups; this was simply the version that was to go on display in the Smithsonian…” Everyone in that basement sat with rapt gazes at the television, all wondering the same thing. Who would steal the official copy of the DSM-8?

Morrison sat at his table, the pills from yesterday replaced by a large glass of bourbon. He stared loathsomely at a giant tome on his kitchen counter. The title read DSM-8. Passion welled in his chest, never before, a toxic cocktail of emotions, combinations he never thought were possible. Scientists had figured out so much about the human system, that magical labyrinth had been solved. Yet what they forgot about labyrinths was that at the center was a monster, so maybe some labyrinths shouldn’t be puzzled out. The monster at the center of this labyrinth was nothing, the nothingness of freedom.

Morrison, unsure of why he was still poring over his coterie of notes, was reading them nonetheless. Some were self-reflections; others were details he’d searched out about the DSM and its history. Information given by the very friend that had helped him steal the copy on his desk. It had been surprisingly easy; they had never anticipated any such event occurring, so with his friend's help, and a week or so of planning, he had gotten a fake badge, which he used to gain access to the very poorly guarded research center where the book was held. Alas, now this theft of his left him in a worse place than before.

He’d found some older copies of the DSM on a slew of banned websites. Fortunately, the same friend helped him with some technological roundabout ways to access the sites and protect himself. His dissatisfaction had not simply sprouted this week, no, rather it had come to a head, particularly this morning when he found a document showing that the American Psychological Association had been purchased in 2021 by the US government. After some serious scandals led the association into disrepute, the Association lost serious funding and donors, allowing the government to bail it out. Making the FPA Federal Psychological Association, and after that, the “canonization” of the DSM-5 had occurred.

Morrison stood up and grabbed the darts from his table, throwing them at the board on which was a printed copy of the very document. It was already poked full of holes; he looked over to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual eighth edition, and the toxic cocktail was poured out once again. What to do, what to do, he thought to himself, how could he make this problem known, how could he let people know of the deception that had occurred here!

Does it even matter? He asked himself; nobody would believe you! As he had jotted down on a napkin, the Labyrinth of the human had been solved. Or at least duped into giving up its center, he gave a chuckle. Now that Morrison had the book, he didn’t really know what to do with it, so ensuring that he was indeed correct, for the fifth time he flipped open the book. He had not been mistaken, and then he sunk into his couch; misery sat on the couch next to him. He couldn’t be sure how long he sat on that couch flipping through thoughts like flipping through channels, staring at the barren wall in front of him, taking occasional sips from the glass. “What do I do? What can I do? Why do I even care? Does it even matter? Does anything even matter? Even if I were to do anything, people wouldn’t really care; there’s no

point to it all anyways. Who am I that anyone would even listen to me? I am no one, the accursed, the crucified.” So, his once great resolve to overthrow this terrible book slowly dissolved, his anger giving way to moroseness. In his mind, he concluded that nothing really mattered now. The mind of the masses was given over; he now knew that his efforts would be in vain. So what did it really matter, he asked himself, he chuckled to himself on the couch.

“Quoth the preacher, ‘vanity of vanities, all is vanity, what profit hath a man in all his labor which he taketh under the sun? One generation passeth away and another generation cometh; but the earth abides forever.’” And he laughed.

Oliver read, “The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth back to the place where he arose.”

“Oliver, what does this all mean? I normally love your readings, but I just don’t get this book?” asked Dan. “It’s just so… so sad, especially after last week’s reading.”

“We’re getting there, Dan, we’re getting there,” he smiled. “Now I am going to skip ahead to chapter two, the end of it, here we go… Yea, I hated all my labor which I had taken under the sun: because I should leave it unto the man that shall be after me. And who knoweth whether he shall be a wise man or a fool? yet shall he have rule over all my labor wherein I have labored, and wherein I have shewed myself wise under the sun. This is also vanity. Therefore, I went about to cause my heart to despair of all the labor which I took under the sun. For there is a man whose labor is in wisdom, and in knowledge, and in equity; yet to a man that hath not labored therein shall he leave it for his portion. This also is vanity and a great evil. For what hath man of all his labor, and of the vexation of his heart, wherein he hath labored under the sun? For all his days are sorrows, and his travail grief; yea, his heart taketh not rest in the night. This is also vanity. There is nothing better for a man, than that he should eat and drink, and that he should make his soul enjoy good in his labor. This also I saw that it was from the hand of God.” He closed the book and grinned.

“Wait, was that supposed to cheer us up?” asked Dan.

Frank commented, “Yeah, Oliver, still depressing,” chuckling a little bit.

“Thoughts?” he asked the now 13 people gathered in his basement.

“Depressing,” said everyone in one way or another.

This brought a smile to his lips, as he looked around at everyone, and he remembered having the same expression when he wrestled with this book years ago. “I’ll admit that it is true this book is depressing, on the outside, but really it is a beautiful book about escaping that very thing.”

“Escaping depression? None of us are depressed?”

“To a certain extent, it is about escaping depression, but more than that, it is about answering the very meaning of life. Or really to consider how one finds purpose in life, how one can find fulfillment here on earth, despite the setbacks and purposelessness of many things here.”

As they were talking, the door opened, and footsteps could be heard descending into the basement. Quickly, everyone hid their Bibles and instead pulled out a state-sanctioned novel, pretending to be part of a book club. Oliver looked over to the man walking down and found it to be his brother, Morrison.

“Michael… What, ah, what are you doing here?”

“Not happy to see me, brother?”

“Please don’t stop your reading, that is after all why I’m here.”

“To join our book club?” asked Dan.

“Oh, don’t treat me a fool, I know what it is you are all doing down here, and no, I will not report you to the FPA. You see, brother, once again you have put your ample mind to work and come to the wrong conclusion.”

“How so?”

“You quoted Ecclesiastes, yes?”

“What do you know of the Bible?”

“I know enough to know that your conclusions are wrong.”

“Why is that?”

“‘For all this I considered in my heart even to declare all this, that the righteous, and the wise, and their works, are in the hand of God: no man knoweth either love or hatred by all that is before them. All things come alike to all: there is one event to the righteous, and to the wicked; to the good and to the clean, and to the unclean; to him that sacrificeth, and to him that sacrificeth not,’ tell me, brother, how might you justify that? It’s pretty plain…”

“‘Go thy way, eat thy bread with joy, and drink thy wine with a merry heart; for God now accepteth thy works. Let thy garments be always white; and let thy head lack no ointment.’ Two verses down, brother, you must read it all.”

“Ah, indeed, but here is when you made your mistake because you didn’t let me finish. How can this be justified whilst God is dead? If he ever existed at all?”

“Tell me, what was the manner of his death?”

“Death by 7 billion cold hearts, death by new and shining things, death by lack of attention, death by amnesia. We have forgotten his name, and so he has ceased to exist, out of sight, out of mind?”

“What if we learn it again?”

“Can a corpse of 100 years be revivified, no, brother, he had been too long dormant.”

“Yet, how can a man who never existed die?”

“Ah! Brother mine, now you ask the interesting questions, ‘Whither is God?’ no?”

“So now you quote madmen?”

“Madness and geniuses go hand in hand.”

“No, madness gives the appearance of genius, but it is still madness.”

“Say what you will, has God ever existed? That is what I came to ask you, to seek wisdom with my mind, to understand. To do that which seems to be such folly to this man, the Preacher.”

“Why do you say that God never existed?”

“Simple observation suffices, look at the wickedness in the hearts of man? Their folly and their cruelty? How can it be said a good God did this? If, and I mean if, God created the world, then he was twice proven an imbecile.”

At this statement, a gasp traveled across the room as the people heard him speak such blasphemy. Oliver was not riled, though; he was used to the behavior of his brother, his tendency towards the grandiose was renowned.

“God an imbecile, brother?”

“If he created such a world, yes, such stupid and pitiful creatures, with deception buried in their hearts.”

“I think you give God too much credit for another’s deeds, Michael, and you forget our real enemy, Lucifer, moreover ourselves. I think we do a nice job of corrupting our own lives.”

“Then why does he allow it?”

“Why shouldn’t he?”

“Because…

because it’s bad, it is harmful, and wicked…” he petered out, surprised by the response.

“Why suffering and hardship, all of those things?”

“What do you mean why? It’s suffering; people shouldn’t have to endure that.”

“Brother, tell me, you are a successful and smart man, was school easy for you?”

“Not necessarily, I failed an exam or two.”

“Ah! Then why did not your teacher swoop in and save his class from the hardship of studying and give the whole class an A? After all, they should not have to have endured a hardship!”

Dan chimed in, “Or to build muscle, one must exercise. If you stopped when it got hard, you’d never get stronger.”

Morrison recovered his wits. “Ah yes, friends, but that is an entirely different kind of suffering. See, I chose to exercise, and I chose to go to school. I did not choose this place, this habitation on earth.”

Now Oliver cracked a grin. “Ah, brother, now are you saying that true enlightenment is the realization that the answer to life is death? Since I do not deserve suffering and the world is nothing but hardship, the only way to stop the suffering is to… stop living? I thought you a man of education!?”

“I’ve not said that!” exclaimed Morrison.

“Oh, well then tell me, just what did you mean by that statement then? If to live is to suffer, how does one stop suffering?”

“To stop suffering is the very question. I’ve posited no solution, merely that the existence of evil must necessarily disprove a good God, not even that there is a God. I am more convinced now than ever that God exists but only that he is cruel and uncaring.”

“Brother, why are you here? I am happy to see you, of course, but what are you doing? Have you simply come to argue?”

At this, Morrison finally sat down, his head in his hands. “I am seeking the truth, but what that is I know not. I cannot work out what is real and unreal, true and untrue. I am seeking something, and I cannot find it. Why even I am seeking that I cannot say either. Yet in my heart, I know that I should seek it, but there again I question. My mind disagrees with what my heart knows, but does not your own book say that the heart is deceitful and above all desperately wicked? So, there is this thing that I seek and cannot find. Yet should I even look for it?” he paused and thought. “Then again I ask, why seek after truth at all? Your preacher says that man shall die, and it is better to be a living dog than a dead lion, for the dog is living. And if man’s fate is death, then why at all should I care what I do in life? Why must there be something that is actually true if it is only true for a little while?” Again, Morrison groaned, and his head was back in his hands, his confidence evaporating under the weight of his own questions and confusion. “My whole life I have lived by the color of the law, but for what? Why? What does it even matter?” He paused for another few moments. “First, it was your God’s law, when we were boys. But when I went to war, well… you know what happened, what I saw. When I got back, you also know what I experienced. Then the DSM was published, or should I say codified, and it made sense to me! They explained so much about humans; it only made sense to ensure people adhered to it. I did everything it said, even went back to school to be educated, as it said to do, education fixes everything it says. But now, I just don’t know, the medicine they give me doesn’t help, their advice keeps changing, and I refuse to be deceived by them! I will not be lied to; I will not be hogtied by an invisible law that I cannot see!” Morrison finally finished his tirade and sat back in his seat; coffee was brought out, and he accepted one.

Everyone was waiting with bated breath to hear how Oliver would respond to his line of questions. “I pity you, Morrison, and I sympathize with your predicament. You’ve asked so many questions that you cannot find an answer by reason any longer. For the next answer to your next question, you will say, ‘Well, what about this? What about that?’ Because when you constantly question with reason subjected to nothing, you only find the response ‘It’s not that.’ Your mind cannot puzzle out all of reality; that is what Solomon was saying. Reality is too big for our small minds to solve. When you attempt to question everything, it does not end well. Yet I will tell you what you seek; you seek the Love of God; you are seeking to be loved. This DSM book, it says that happiness comes from the gratification of the flesh. To live is to be happy, and to be happy is to live. Therefore, what makes me happy keeps me alive, and if I am unhappy, then I must be near to death. Psychologists would have us believe that the goal of man is to reach “Self-Actualization,” a farce as pure as any farce.”

“How so, brother? Should I not learn about myself to reach my full potential?”

“Can a ship steer itself? Let loose its own sails? Perhaps, if it were constructed in the sea sails already down. The natural course of things, the boat would sail for days, perhaps months; who knows, maybe for years even. It can wander the ocean, flying across the water. In this, has the boat not self-actualized? Has it not found its intended purpose to sail the ocean?”

“Well, it was meant to take people across the ocean,” responded Morrison.

“Yes, it was, in fact, it matters not that the boat can sail by itself; it was not meant to. So truly, it has not self-actualized because one cannot self-actualize. Especially if we have gotten rid of God, if we do not believe that we were, just as the boat was, designed for some purpose, we cannot figure out what that was. If we are here by the course of random atomical collisions, then we cannot have self-actualization, we cannot have love because all these things are meaningless. And Nietzsche was right, there are no moral phenomena, just moral interpretations. Everything is subject to interpretation. God is required to give us purpose; God is the one who actualizes us. Without God, there can be no morality and no realization as to why we are here. It is, in fact, natural to wonder ‘who made me?’ somewhere along the way, Satan whispered in our ears ‘no one’ and we believed him. Now we see the repercussions.”

“Well, now the Psychologists say whatever they want,” replied a forlorn Morrison.

Oliver looked inquisitively at his brother, and Morrison saw the look. He pulled out of his bag the blank DSM. He tossed it onto his brother’s lap. When Oliver recognized the title, he looked at Morrison with surprise. “You stole the book?”

“I did.”

“Why?”

“I don’t remember, I had a reason at some point, but I’ve now forgotten it, something about… sending a message.” He thought. “I wanted to make a sign or

a symbol, let people know that they are all liars. Yet I realized… ha… ‘this too was vanity’ the people will never believe me. They now desire to be lied to, they’ve so thoroughly been taken in. The government is corrupt, it is evil, and the people need to be shown somehow. What was it our founders said, ‘the tree of liberty must from time to time be bathed in the blood of patriots and tyrants’ right? Yet how does one tear someone from his favorite thing, his favorite glutton’s appetite?”

"Brother, I do believe you are an enigma! Tell me, you don’t believe in truth, so why do you believe that what you did was right? What does that symbol matter if nothing means anything? If nothing means anything, brother, why does it matter if people follow a blank book? If there is nothing before us, nor after us, well then there is no goodness, therefore no evil, therefore no corruption. Our government is not corrupt, it is, in fact, just different. Different than before, yet no better nor worse because no ideals exist for which to measure it.”

“But we have had better governments, look to our founding? Is that not better?”

“How can it be better? Sure, by our own standards, but what are those standards other than fanciful notions? Misplaced ideals in something that isn’t actually there; without God, there is no good, and without good, there is no better, not best, only different.”

“Yes, I suppose that is true, and I suppose that is really why I came, though I did not know at first. What do I do with this book, brother? I grasp at straws, yet even the straws are made of smoke. What do I do?”

“You cannot remove a speck from someone else’s eye before removing the plank from your own eye first. If you ask me, brother, you must battle your demons, then you must wrestle with God, and let him win.”

Morrison was outside again; it had begun to snow this particular morning, so the sky was dark. Yet Morrison was going for a walk. He did not know where; he was just walking, the exercise and fresh air were nice. He often liked to walk when he was trying to puzzle out a problem, something about the air and the movement. In the course of his walk – he’d long since lost track of how long he’d been walking – he found himself in the poorer area of town. He was suddenly jolted from his thoughts as he stopped and saw the children playing. They were laughing, not a care in the world; they giggled and laughed, their grandparents sitting on the porches watching with quiet smiles. As he watched, it was as though the sunbeam that cut through the dark clouds touched his soul. Something sparked to life in him, something long dead or at least dormant. He thought to himself, how can these people be happy? He didn’t know; here it was snowing and cold, yet these kids were outside, they were in obvious squalor. Their coats bedraggled and their faces gaunt, yet they did not care. They played, the slew of grandparents watching their grandchildren all had smiles, some chatted together with lively speech. Others simply sat in pleasant adoration of their offspring. None bemoaned their plot in life, non-questioned the cruel hand of God for their misery.

The narrator of this story has not up till now spoken directly to you, for it was not necessary. Yet as our story comes to a close, there must be impressed something to the reader: it was not that day that Morrison’s soul was saved. Nay, neither the day after, nor was it the year after. No, this day brought but a spark to his heart, something that just might bring a flame. It would take Morrison many more years before that happened. Alas, it would, in fact, take him many years in prison. For when he left that neighborhood, he knew that he had to do something; he had to make a symbol for all of the people.

Oliver was watching the television, only because he had heard that a big story was going to be broken, he feared he knew what it was. The news anchor (of a relatively small channel in the local area) introduced Morrison. Morrison had actually appeared on the show once before for things related to his field of work. Oliver saw the picture of his brother come into view; he was sitting in his home with the fireplace on in the background.

Oliver could barely hear his brother; his mind was so muddled as his brother explained to the anchors what he had heard nearly two weeks ago now. The two news anchors were both shocked and horrified. Yet very thoroughly Morrison explained how he’d stolen the book, how the book was real, and how everything they were being told was a farce. Then symbolically, Morrison threw the book into the fireplace behind him. At that moment, Oliver dashed off to his brother's house, missing the closing remarks.

“The book is a lie, I tell you! A lie, it is futility to listen to them! Futile, I say. The Book is a lie, so now the deed is done, the book is burned. And you, my friends, we all must rise anew from the ashes of that book. Recognizing it for what it is, a bad interpretation of things we cannot fully understand, knowledge without a soul was what it was, wisdom without a heart, which is no more than folly. I do not yet know how we can recover from this, but it must be dwelling on good things when we can find them. Whatever that good thing is, that must be the start. From there, I have nothing more to offer; I am not posing a solution, merely displaying a problem. The Federal Psychological Association is a sham, we must leave that behind us.” He finished speaking, but the two hosts were left speechless.

Oliver arrived at Morrison's house just in time to see him being escorted out by the police. Morrison looked over to his brother and called out, “forgive me, brother!”

Oliver was lost for words; he had never anticipated this wild change in his estranged brother. The police noticed Oliver but didn’t stop walking him to the car; Oliver shook himself and called out to his brother, “you are forgiven!”

That was the last time Oliver saw his brother, at least for many, many years. Oliver walked to the prison building, 17 years later. The door was ajar, and out walked Morrison, older and grayer, but smiling. He grinned even bigger when his eyes beheld Oliver, and he walked up and hugged him. They both smiled at each other and began to walk back to Oliver’s house.

As they walked back chatting, they passed a large building, and Morrison stopped. “Is that a church?” he asked.

“Indeed, it is, as a matter of fact, that’s my church.”

“You’re a father now?”

“In two ways, yes.”

“So… the churches are permitted again?”

“Indeed, they are.”

“But… How?”

“Well, brother, after your little speech on the news, some people began to reflect. There was no great battle or fight, but it seemed there were some other dissatisfied souls, wealthy dissatisfied souls. Wealthy people have good lawyers, it would seem, and floods and floods of litigations came in. More civil action was required, though, and it took nearly 16 years, but people took a stand, they refused to participate in the lies. We began to hold our meetings in public, some of us were arrested, I was thrown in jail for a month, hardly what you’ve endured, but eventually the jailing stopped. Politicians stepped down; others were arrested. We needed more momentum, though, for the Book and its Psychology endured a little longer, we needed an emblem and signal. So, we started building this;

it took 4 years, but now it’s finished, a symbol for people.”

They stopped and looked at it a little while longer, then Morrison spoke, “that is thy portion in this life, and in thy labour which thou takest under the sun. Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest.”

Oliver looked over at his brother with a smile. “Go thy way, eat thy bread with joy, and drink thy wine with a merry heart; for God now accepteth thy works…”

“Indeed, he does…”

THE END